A great piece of enterprise reporting by Tom Clynes — part profile, part essay, part investigative journalism — that celebrates the heroic effort by one man to protect endangered species in the Congo. This was my first project for Conservation Magazine (story concept and development), and one of two that was featured on the cover.

By Tom Clynes

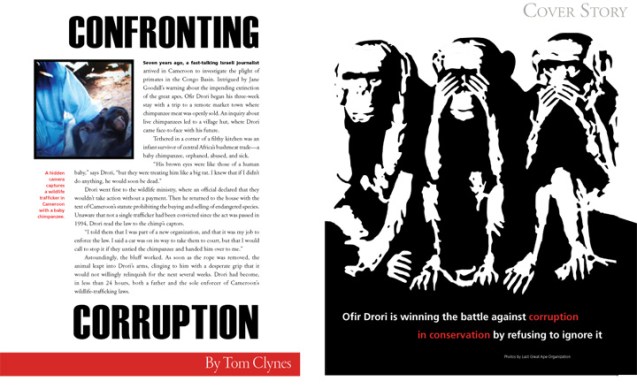

Seven years ago, a fast-talking Israeli journalist arrived in Cameroon to investigate the plight of primates in the Congo Basin. Intrigued by Jane Goodall’s warning about the impending extinction of the great apes, Ofir Drori began his three-week stay with a trip to a remote market town where chimpanzee meat was openly sold. An inquiry about live chimpanzees led to a village hut, where Drori came face-to-face with his future.

Tethered in a corner of a filthy kitchen was an infant survivor of central Africa’s bushmeat trade—a baby chimpanzee, orphaned, abused, and sick.

“His brown eyes were like those of a human baby,” says Drori, “but they were treating him like a big rat. I knew that if I didn’t do anything, he would soon be dead.”

Drori went first to the wildlife ministry, where an official declared that they wouldn’t take action without a payment. Then he returned to the house with the text of Cameroon’s statute prohibiting the buying and selling of endangered species. Unaware that not a single trafficker had been convicted since the act was passed in 1994, Drori read the law to the chimp’s captors.

“I told them that I was part of a new organization, and that it was my job to enforce the law. I said a car was on its way to take them to court, but that I would call to stop it if they untied the chimpanzee and handed him over to me.”

Astoundingly, the bluff worked. As soon as the rope was removed, the animal leapt into Drori’s arms, clinging to him with a desperate grip that it would not willingly relinquish for the next several weeks. Drori had become, in less than 24 hours, both a father and the sole enforcer of Cameroon’s wildlife-trafficking laws.

During the long bus ride back to Cameroon’s capital, Yaoundé, with the chimp resting in his arms, Drori came up with a name for his fledgling law-enforcement NGO—the Last Great Ape Organization (LAGA)—and for the rescued chimpanzee.

During the long bus ride back to Cameroon’s capital, Yaoundé, with the chimp resting in his arms, Drori came up with a name for his fledgling law-enforcement NGO—the Last Great Ape Organization (LAGA)—and for the rescued chimpanzee.

“I decided to call him Future,” he says, “because that’s what I wanted to give him.”

Unable to find a facility that could care for Future, Drori brought him first to a zoo, sleeping in his cage and comforting him through his many nightmares. Then, the two moved into a rented apartment near the forest. As Future began to recover, Drori went back to the village and recruited the chimp’s captors as informants. It took time, but he eventually found a sympathetic officer in the police department and one in the wildlife ministry. He enlisted these men, and other volunteers, to work as undercover agents—outfitting them with hidden microphones and cameras.

Over the next several months, Drori and his team staged dozens of high-risk, often-violent operations, teaming with the police to bust bushmeat dealers as well as traffickers dealing in live apes, African gray parrots, ivory, and the meat and skins of everything from leopards to rhinoceroses.

“I made a lot of enemies those first few months,” says Drori, “but in terms of stopping the illegal wildlife trade, I was getting nowhere.”

From the moment of their arrests, the traffickers would work the system—sometimes simply paying a bribe and walking out of jail, sometimes having contacts in government “evaporate” the case. As for the confiscated contraband, it usually found its way back onto the market.

“I realized that I had arrived into a system where the law barks but it doesn’t bite,” says Drori. “And so, I began to understand that I would need to go beyond the wildlife itself and attack the root of the problem, the major thing that is holding back conservation around the world: corruption.”

. . .

Social scientists have long understood that corruption has disastrous effects on struggling economies and people, with the poorest suffering the brunt of that impact. What is now becoming clearer is corruption’s devastating impact on ecosystems—and on the business of conservation itself.

In the Congo Basin, bushmeat consumption likely exceeds 1 million metric tons per year—the equivalent of about 4 million cattle. Worldwide, loggers last year illegally harvested more than 100 million cubic meters of timber, felling enough contraband logs to stretch around the earth 10 times. Illegal commerce of threatened and endangered species has grown into the world’s third-largest illicit trade, trailing only drugs and weapons and generating up to $20 billion in revenue.

“Whether it’s high-profile embezzlement or a low-level bribe to a petty bureaucrat, corruption has become a major force undermining environmental equity and destroying ecosystems,” says the World Resources Institute’s Gregory Mock.

Field staff at some NGOs may compound the problem by paying out small bribes, believing that their work would otherwise be more difficult or impossible. Meanwhile, corrupt officials enable resource extractors to disregard regulations, ignore quotas, dodge taxes and export duties, and harvest beyond boundaries. This in turn deprives cash-strapped governments of revenues, devastates the livelihoods of resource-dependent people, and fosters a cycle of continued corruption and conflict.

“Conservation projects keep failing, one after another, because of this one issue,” says Robert Barrington of Transparency International (TI). “And yet we don’t plan for it, understand it, or know how to design it out of projects.”

Discussing the influence of corruption on conservation is a bit like bringing up religion or politics with a new neighbor. The subject remains somewhat taboo—possibly because some in conservation view it as a necessary evil while others say it is too big a beast to fight, much less clearly understand.

“The conservation community is still loath to talk about it,” says Barrington. “But evidence is emerging that corruption may be the hidden time bomb in conservation.”

The World Bank Institute and TI estimate that more than $1 trillion is paid in bribery globally, with tens of billions of dollars changing hands each year in sub-Saharan Africa alone. The location is not a coincidence.

While corruption affects all societies, the incidence is highest in developing nations—which, as fate would have it, contain much of the world’s biodiversity. Countries with unstable governments are most vulnerable, but the world’s richest, most stable countries are not immune. For example, economist Per Fredriksson of Southern Methodist University has used theory and data to show that corruption reduces the stringency of environmental laws in the U.S. and other highly developed economies.

But other research shows that corruption can be a double-edged sword.

“Corruption can actually have positive impacts on biodiversity conservation when it negatively impacts the efficiency with which economies destroy natural systems,” says Christopher Barrett, an agricultural and development economist at Cornell University. Barrett cites his own research in Madagascar, where theft of road-building equipment and funds kept large blocks of forests inaccessible for years.

Fredriksson and Robert Smith of the University of Kent’s School of Anthropology and Conservation are among the few researchers who have attempted to quantify corruption’s toll on conservation efforts.

“But because corruption takes place away from public view,” says Smith, “hard data is extremely scarce, so it’s difficult to get a grip on what’s going on.”

Thus far, a clear causal model of the mechanism by which corruption affects resources has proven elusive. Generally, though, most comparisons of environmental-sustainability indexes with national corruption indexes (such as TI’s Corruption Perceptions Index) support the theory that the more corrupt a country is perceived to be, the poorer its environmental performance. Unfortunately, such national-level indicators have limited utility, since they fail to account for the fact that corruption is a highly localized and inconsistent phenomenon.

. . .

Even scarcer than conclusive theories and data are examples of conservationists who have managed to tackle the problem of corruption head-on. Among them, Ofir Drori would have seemed an unlikely candidate when he landed in Came-roon in 2003. With his long and tousled hair, his dark moustache and goatee, and his penchant for wearing all black, the thin-framed Drori could pass for a 1970s-era Frank Zappa.

Drori’s parents sent him to an experimental, nature-based school and encouraged an adventurous, risk-taking nature that became apparent at an early age. After serving as an officer in the Israeli army, Drori founded an educational program to foster tolerance in his native land. He set off for Africa in 1999 and spent the next four years exploring and writing. He trekked though Kenya on a camel and through Ethiopia on a horse. He descended the Niger River in a canoe and spent months living with remote tribes in Nigeria. When rebels attacked Freetown, Sierra Leone, Drori was there.

Emotionally exhausted after filing a report on the stoning of women in northern Nigeria, Drori headed for Cameroon “to take a break from the real stuff,” believing that a story about disappearing apes would be relatively undemanding. At the time, he had little interest—and no experience—in conservation.

“Looking back now, I think that was a good thing,” he says. “I didn’t need to inherit the old approaches and conventions. With fresh eyes, I could see what the conservation NGOs in Cameroon were doing. And I could see that it wasn’t working.”

What Drori saw was underpaid—and in some cases, unpaid—game guards at reserves, accepting bribes from poachers who supply restaurateurs with ingredients for local delicacies such as chimpanzé à la sauce tomate. He saw employees at NGOs inflating expense reports. He watched public confidence collapse when one Cameroon-based NGO was exposed as a front for an illegal immigration scheme.

“Mostly, I saw a lot of money pouring in from donors, and no results. No one was demanding that the government enforce their own laws.” Drori envisioned “a conservation experiment” that would mix successful strategies from around the world with his own innovations. He imagined LAGA as a low-budget, high-intensity reaction to the large NGOs that, in his opinion, had become corrupted by big budgets and were stalled in a cycle of failure.

Around the world, successful strategies to combat corruption usually involve action on several fronts. At the national level, engaged leadership is important, since corruption can’t thrive under the scrutiny of strong mechanisms of accountability—such as independent audits, watchdog groups, thriving political opposition, and a strong and free press.

Brazil’s experience illustrates the potential for conservation gains when governance improves. As recently as 2004, loggers and farmers were wiping out Brazil’s forests at a rate of about 2.5 million hectares per year. Now that’s down to 400,000 hectares.

“It’s true that the financial crisis decreased demand somewhat,” says William Laurance of the School of Marine and Tropical Biology at Australia’s James Cook University, “but you have to credit Brazilians for better enforcement. They’ve developed a system that’s cutting-edge, linking real-time satellite data to landowner information, with mechanisms to follow up with on-the-ground action.”

Brazil’s heavy-handed “Arc of Fire” operation in 2008 was one of the largest enforcement actions ever launched against illegal logging, with hundreds of inspections and seizures at sawmills across the Amazon basin.

Such high-profile operations can send a message that government is serious about environmental protection. But what about a place like Cameroon in 2003, where—on paper—wildlife laws appeared to offer a formidable means of protection, but where leaders lacked any will to enforce them.

“In that case,” says Drori, “you create that will. You make that part of your mission.”

. . .

Realizing that the wildlife traffickers he was busting were essentially immune to punishment, Drori assigned teams to shadow suspects as they made their way through jails and courthouses. Persevering through threatened (and often real) violence, the monitors would follow every step of the legal proceedings, documenting bribery attempts, phone calls, meetings—anything that suspects might use to get themselves off the hook.

Realizing that the wildlife traffickers he was busting were essentially immune to punishment, Drori assigned teams to shadow suspects as they made their way through jails and courthouses. Persevering through threatened (and often real) violence, the monitors would follow every step of the legal proceedings, documenting bribery attempts, phone calls, meetings—anything that suspects might use to get themselves off the hook.

Next, Drori enlisted the press and international communities to publicize cases, pressuring Cameroon’s notoriously corrupt judiciary to follow through with prosecutions.

“The last thing the government wanted was to embrace what we were doing,” says Drori. “Their tactic was to ignore it. But we wouldn’t let it die. We’d supply pictures to the newspapers, and we’d invite the television stations to come with us on busts. We’d see that the minister in charge would get letters and phone calls and faxes from anywhere and everywhere. We’d have journalists come to his office five days in a row and demand a statement. We’d push the government to the point where they finally could not be neutral. They would have to publicly embrace what we were doing.”

The strategy was extraordinarily labor-intensive—Drori says he typically slept four hours a night—but finally, seven months after LAGA was founded, the organization scored a victory: the first prosecution of a wildlife crime in Cameroon’s history.

In the days following the conviction, Drori saw to it that Cameroon’s leaders received a flood of congratulations from governments and NGOs all over the world. That support, combined with the flurry of internal media coverage, brought about a crucial shift in the political environment. Suddenly, it was popular for politicians to get behind wildlife protection.

Emboldened by the government’s growing support, LAGA began to go after bigger fish, raiding networks of bird smugglers, closing down ivory workshops, dismantling a network of traffickers that extended from Cameroon to Hong Kong.

Although LAGA investigators document bribery attempts in more than 80 percent of their cases, 87 percent of the suspects are now denied bail and put behind bars immediately after their arrests. Judges have fined traffickers up to $35,000 and handed down prison terms of up to three years. LAGA investigations have also brought down officials who enabled wildlife crimes—mayors, police commissioners, ecoguards, magistrates, army officers, and even the secretary-general of the Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife.

As LAGA’s high-profile successes mounted, informants reported that traffickers were running scared. During one sting, a LAGA agent recorded an ivory dealer warning another of “a dangerous white man in black with long hair, who uses strong magic.”

. . .

Cameroon’s legal system now averages one prosecution per week against wildlife dealers, most of them caught in LAGA-initiated snares. And LAGA has attracted grants from more than 20 funding sources, including the US Fish and Wildlife Service, Germany’s Pro Wildlife, and the Born Free Foundation.

But for Drori, getting the government to take environmental crimes seriously wasn’t enough. To get to the heart of the problem, he needed to involve ordinary Cameroonians in the fight against wildlife trafficking.

Barrington and other experts say that the most important—and most difficult—step in reducing corruption is changing public expectations. In developing countries, poor pay and low social status may tempt some officials into corruption, but cultural attitudes and expectations about the privileges of

authority also often play a part. In much of Central Africa, for instance, officials often make little attempt to hide corrupt habits, believing they are entitled to the benefits they receive. Unless illegal practices are seen as unacceptable to both practitioners and the public, anti-corruption laws and procedural reforms may have little effect.

After their first high-profile prosecutions, Drori and his allies hit Cameroon’s television and radio talk shows in an effort to change public attitudes.

“We said that the huge price tags for dead or caged animals endanger the country’s wildlife and benefit only individual pockets,” Drori said, “while the benefits of ecotourism can be shared by an entire nation.”

Promoting awareness of environmental issues is a proven strategy for conservation. But in a place like Cameroon, where 79 percent of the population reported paying a bribe in 2007, Drori realized that he needed to go further.

“Sensitizing the public to the fact that this problem exists and needs to be fought has little value if people aren’t empowered to take action against it,” says Drori. “Corruption in Cameroon relies not so much on the inability to know as on the inability to act.”

In 2008, Drori founded a new organization, Anti-Corruption Cameroon, to assist Cameroonians who want to fight against corruption. The organization’s “Kick Corruption” website boasts: “If you were hurt by corruption we will fight for you, not only to try to get your money back, but [also to] get compensation and above all get the corrupt person to justice.”

Unfortunately, Anti-Corruption Cameroon has yet to achieve its first conviction.

“We’re getting 30 phone calls a day on our hotline from victims,” says Drori. “But like the early days of LAGA, it is a struggle. We spend so much time grouping victims to stand up as one against a corrupt official, but then if one person is threatened and gets cold feet, the others turn back, too.”

Now, Drori is pinning his hopes on two cases in which he has mobilized members of Cameroon’s taxi-driver syndicates to take on police inspectors who extort them for bribes.

“They are working their way through court, and maybe we will have a prosecution soon,” says Drori. “But the bottom line is we still have not delivered what we need: a landmark prosecution in which the poorest people of this country get a big corrupt official into jail. That would be a big step that would make this part of the world a little bit better.”

. . .

Drori has ruffled feathers in the conservation community by insisting that international NGOs bear much of the responsibility for the problem of corruption in Central Africa.

“International aid is big business here,” says Drori. “Members of the international community need to be more transparent, and they need to take the lead by refusing to pay bribes, even if they provide an enticing shortcut to deliver services.”

Indeed, even as more governments and international businesses move toward intolerance of corruption, nongovernmental organizations remain among the least transparent and most poorly monitored of all sectors.

“Ask any large company for its bribery policy, and the good companies will have a document,” says Transparency International’s Barrington. “Ask someone working for a big NGO in the developing world, and they’ll likely tell you that if they didn’t pay occasional bribes, they couldn’t operate—which is essentially what a bad company would say. And yet, if you got them in a room and talked about the problems bribery causes they’d be dead-set against it, because it undermines their own mission.”

The problem, Barrington believes, is that the average NGO professional doesn’t have the skills to say no.

“That’s a leadership issue,” he says. “NGO leaders need to stop sweeping the problem under the rug and help their people learn how to get their jobs done without contributing to the problem of corruption. There are organizations that can help them.”

Beyond undermining individual programs, revelations of corruption have the potential to hurt conservation fundraising across the board. Last year’s disclosure of corruption within the UN’s Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) program in Papua New Guinea—in which tribal landowners say they were coerced at gunpoint to sign away carbon rights to their forests—illustrates how quickly a scandal can jolt international donors’ confidence in environmental programs.

. . .

Lately, Drori has been traveling abroad again, sometimes as part of Cameroon’s CITES delegation, sometimes as a consultant on wildlife law enforcement issues. Although he has been asked to open LAGA branches in other countries, Drori says he would rather support and collaborate with conservationists in neighboring nations, to help them develop home-grown capabilities.

Lately, Drori has been traveling abroad again, sometimes as part of Cameroon’s CITES delegation, sometimes as a consultant on wildlife law enforcement issues. Although he has been asked to open LAGA branches in other countries, Drori says he would rather support and collaborate with conservationists in neighboring nations, to help them develop home-grown capabilities.

Last year, inspired by Drori’s successes, activists in Brazzaville formed an NGO called PALF (Projet d’Appui à l’Application de la Loi sur la Faune) to build the Congolese authorities’ capacity to enforce wildlife laws and eliminate corruption. In the Central African Republic (CAR), LAGA teamed up with local conservationists to help police make the first ivory-trafficking arrests since CAR passed a wildlife-protection law in the 1980s.

“And in Gabon,” says Drori, “we hope to have our first arrests next month.”

If LAGA’s success has boosted Drori’s confidence, the unrelenting stress has affected him deeply, ruining a marriage and, friends say, leaving him burned out and increasingly impatient and brusque.

“Ofir is one of the few people who have the temerity and ability to get important things done,” says Richard Ruggiero, of the US Fish and Wildlife Service. “But he pisses people off. He’s made enemies with all the bad guys; where he needs to be careful is not to make enemies with the good guys.”

If Drori’s intense, uncompro-mising approach could misfire anywhere, it’s likely to be in Gabon, where the government has taken tentative steps to promote conservation and root out corruption.

“It’s true that change isn’t happening fast enough,” says one conservationist working in the region. “But the danger is that too much pressure at the wrong time could get the leadership turned off from conservation.”

Seven years after arriving in Cameroon, chronic malaria has thinned Drori’s face and lifted his cheekbones. His eyes are surrounded by shadows of exhaustion, but they light up when he responds to a question about the most enjoyable part of his job.

“It’s when we rescue a baby ape,” he says. “I get to spend a little bit of time with them, and I feel connected back to the reason I started all this.”

As for Future, Drori eventually found him a home at the Sanaga-Yong Chimpanzee Rescue Center, where Future now lives with his adopted chimpanzee family.

“Next year, there’s a good chance that he will be ready to be re-integrated into the wild,” says Drori. “You could say that I’m a very proud father.”

And as for the story that first brought Drori to Cameroon—the one he planned to write about the impending extinction of the great apes?

“It’s still half-finished,” he says. ❧

Writer and photographer Tom Clynes covers science and international environmental issues. Tom is the author of Wild Planet; he also contributes to Popular Science, Men’s Journal, The Times of London, GQ, and many other publications.

Photos by Last Great Ape Organization

UPDATE: Drori’s efforts recently exposed a 4-nation wildlife smuggling ring:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2010/dec/12/africa-wildlife-ivory-smuggling